5 A Methodology for Agile Data Science

Now that we have interpreted the Twelve Agile Principles in the data science setting, we explore what an Agile data science workflow might look like. Let us remind ourselves that an Agile workflow is always a means to an end. The Agile values and principles are the guidelines and the workflow follow them as closely as possible. If at any moment in a project the team feels the workflow is no longer the optimal way to make decisions in an Agile way, they should change it. This chapter should be considered as an exploration, a bunch of thoughts. If some of it does not work for you for whatever reason, by all means find a better way.

5.1 Linear and Circular Tasks

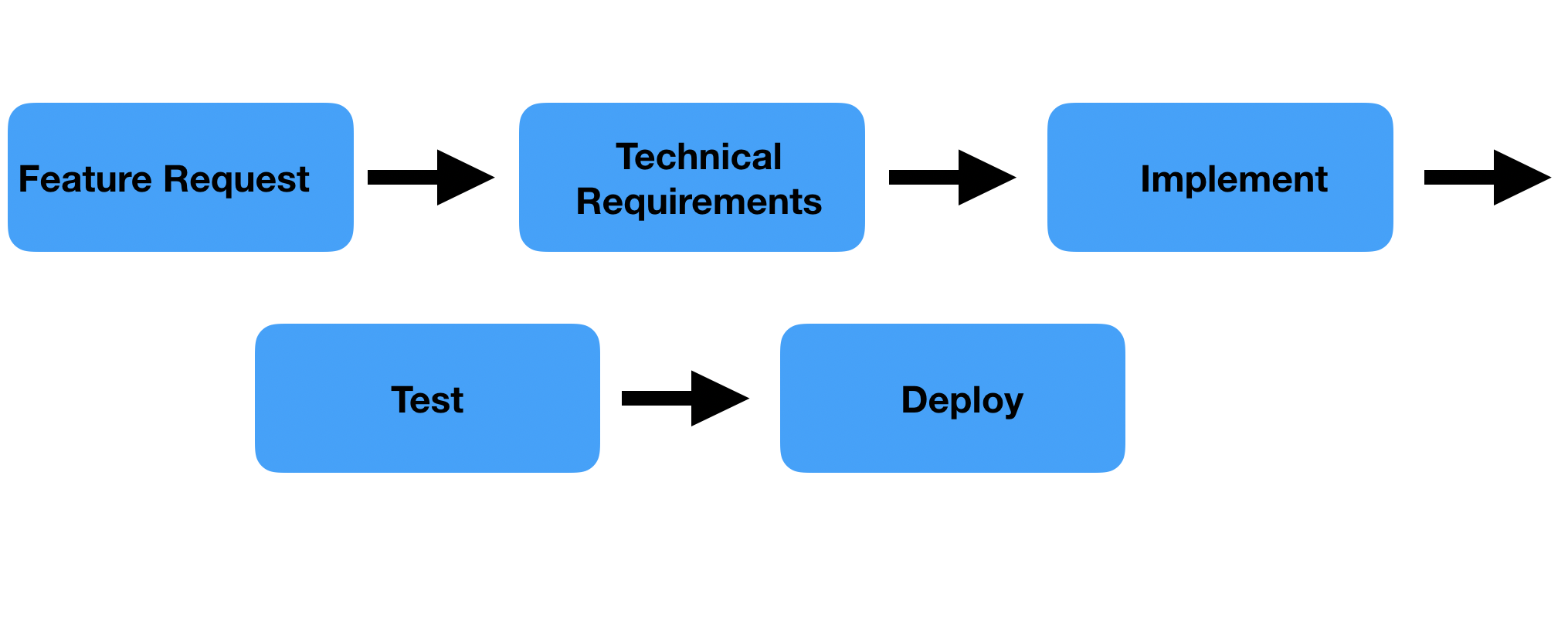

The tasks in Agile software development are what I call linear tasks. They come from product feature requests by stakeholders or ideas within the team itself, collected by the product owner. The envisioned outcome is captured in a user story. The team translates it into the technical tasks and starts working on it. Neither Scrum nor Kanban prescribes the steps a task should go through, but it typically looks like the following.

Figure 5.1: Linear flow in software development

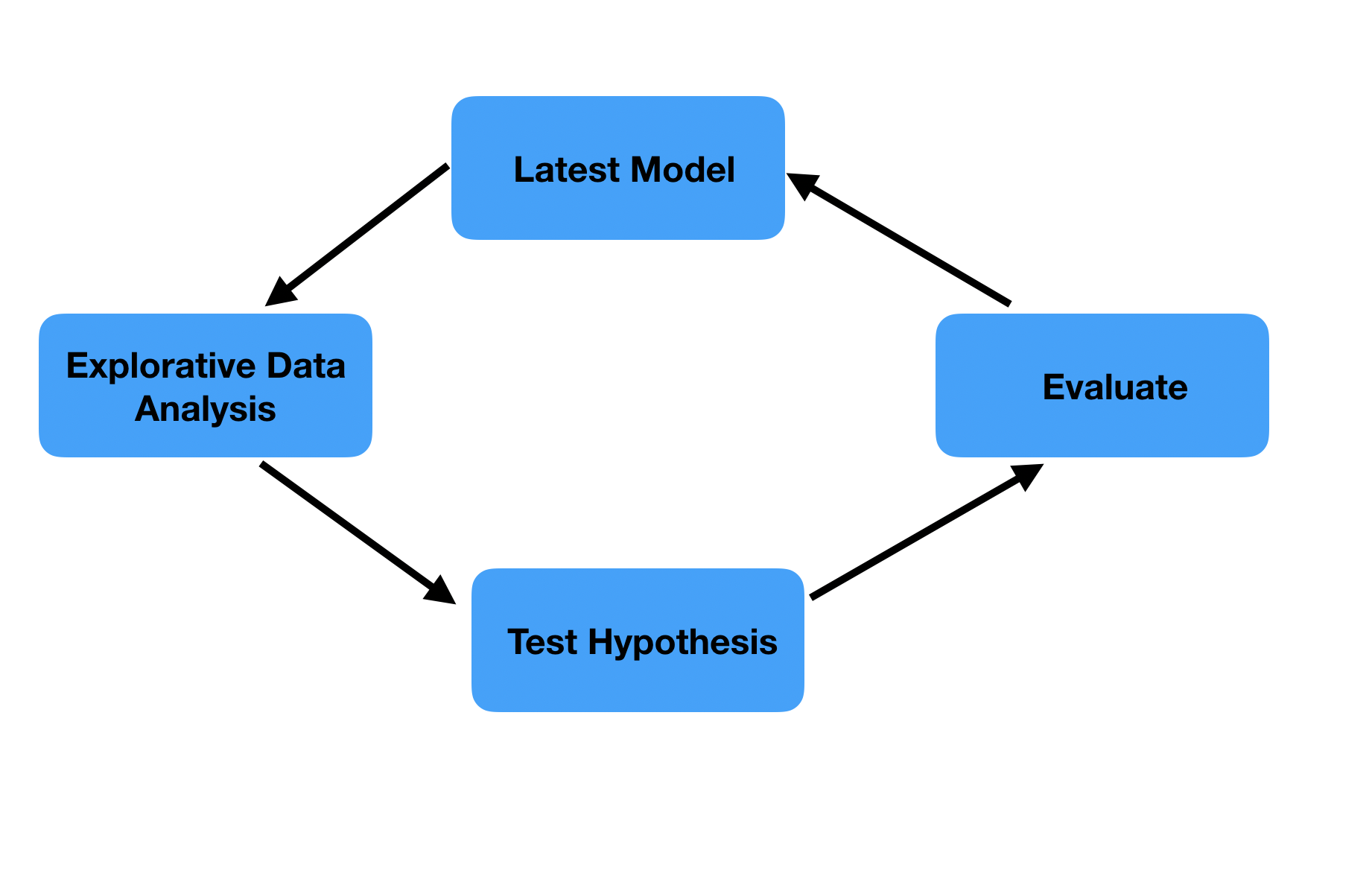

These types of tasks lend themselves well for scoping and committing oneself to what the product will look like in a few weeks time, as is done in Scrum. (Note that the tasks are typically linear, the entire process of building a product is iterative by nature). In contrast, data science tasks are circular, as at first it is uncertain what the outcome will be. The starting position is the latest version of the product. If one has not yet a good idea how to further improve it we would typically do an explorative analysis in which a hypothesis can be formed. This hypothesis is then tested. We evaluate if we can improve the product based on the hypothesis tested. If so we improve it and then go on with the next hypothesis. Otherwise, we go on with the next hypothesis right away.

Figure 5.2: Circular flow in machine learning

Data science projects also encompass linear tasks, such as setting up a pipeline to import the data and do basic data wrangling, creating apps or exposing the model results in an API. However, the circular nature of leveraging relationships between variables makes the highly structured Scrum method unfit for most data science projects. We simply cannot guarantee that a statistical model or a machine learning algorithm will be improved in two weeks time, because we don’t know if the hypotheses we are going to test will lead to anything. If we had committed to a set of tasks for a fixed time period from which we cannot deviate, we are slowed down because we cannot directly act on newly gained insights.

Data science encompasses a broad array of project types. Maybe some don’t have circular tasks at all and are basically software development projects. Examples might be building an app on a known data source or automating reports to be sent out every month. For these type of projects it might make sense to follow a Scrum, cutting up work into user stories that are implemented in fixed time intervals. Most data science projects however, will have a mixture of linear and circular tasks. For any project with circular tasks the flexibility of Kanban is preferred over the highly organised Scrum. In the remainder of this text we assume projects to be at least partially developed using relationships that are unknown at the start of the project, and thus contain circular tasks. If this is not applicable to your situation, you might find literature on regular Agile software development more appropriate.

5.2 A Two-Way Workflow for Development

I propose a two-way workflow for data science product development, in which circular and linear tasks are combined. This workflow makes a hard cut between the data product and exploratory research. The data product is software, and thus built by linear tasks. When starting a task it is clear what should implemented. The data product is complete, which means that it contains all the necessary steps to go from source data to the end result. It can be a pipeline that contains loading, wrangling, pre-processing, modelling, and exposing steps. Or it can be the querying of different databases, joining the different data, calculating statistics and building plots, wrapping everything in a Markdown report. No matter what the product looks like, it should be high quality software so we can rely on it. This will make results completely reproducible and automatable, the two requirements for continuous delivery of improved products. Exploratory research on the other hand can be quick and dirty. In order to test hypotheses quickly, exploration scripts can be interactive analyses without software requirements or even being reproducible in later stages. They should quickly give an indication if the corresponding hypothesis could improve the product.

5.3 Formulating Tasks

In both Scrum and Kanban the tasks ahead are formulated in user stories, clearly stating what the benefit for the customer will be once the user story is completed.

If you try to define a user story for a machine learning model it will always go “As the

5.4 Using Kanban for Data Science

We have concluded that Scrum is too rigid for a data science project with circular tasks, because the explorative nature of data analysis is not suitable for the tight planning of deliverables. Kanban on the other hand gives us the flexibility to change the next task we are going to complete. Within a two-way model for doing data science there is the data product that has to be good quality software and there is the explorative research in which you have the freedom to explore other approaches to come to quick conclusions. You could formulate tasks for the Kanban workflow for both task types. Weaving these two types of work together results in a Kanban workflow with at least the columns to do, doing, and done. Both hypotheses to be tested and planned work on the data product are gathered in the to do column. This is the backlog and it is always ordered from most to least promising, so it is clear what to do next.

Kanban gives focus, finishing one task at a time. Too often when doing data science we have interesting finds on which we jump right away without finishing what we were doing. To prevent that, just add the new find as a hypothesis to the board. This will make sure that the tasks that are currently in doing get completed first, and that after each completion there is a moment where it can be decided what is the most urgent change to the pipeline or the most promising hypothesis to explore next. As a rule of thumb, never work on more tasks simultaneously than the number of data scientists in the team. As mentioned, tasks are either software or research tasks. If the research task results in a proposed model update, the update can be captured in a newly formed software task (which can be placed on top of the to do list right away).

5.5 Scoping Tasks

Scrum uses story points to scope its stories. The team determines the number of points awarded to each story. The team knows how many story points it typically completes in a sprint, so after scoping the sprint can be planned by selecting stories such that the total of their points does not exceed the team’s capacity. Kanban does not scope stories. In fact, the average time of a task’s completion is Kanban’s key metric of effectiveness. When doing data science with Kanban it might still be valuable to scope the tasks ahead, especially for exploring hypotheses. One of the major pitfalls of trying to improve a data science product is endless exploration of a hypothesis. We like to have just one more look from this other angle, or maybe this new fancy algorithm that you are anxious to test for a while will give a major boost. Data scientists are typically assiduous people, this is what allows them to master a wide range of difficult topics from statistics to programming in the first place. However, this could lead to stubbornness, unwilling to give up what was thought the way to get a major improvement. Scoping for data science is then not just estimating how long a task will take to complete, it is also time boxing. If used in this way, the scoping should be done in time units, not in a subjective measure such as story points. The data scientist should not take longer for the task than the team agreed upfront, wrapping up even when he does not feel completely finished. If he found an alleyway that is still worthwhile exploring a new task should be put in the backlog, instead of persevering in the current task. Scoping also helps with prioritising. If there are several candidate tasks to do next, the one with the least time to complete might be best done first.

5.6 The Product Owner Role

When doing software development with Kanban there is typically a product owner involved. She aligns with customers and stakeholders, and add the feature requests in the to do column of the board. For data science engineering it can also be desirable to have someone other than the data scientist doing stakeholder management and communication of the model results. This will free up time and energy for model development. Gathering the tasks to do cannot be primarily laid at the product owner. The data scientist will probably post most of the tasks on the Kanban board, because both hypotheses to test and maintenance work on the data product typically require an in depth knowledge. Product owners can add feature requests to the data products, especially when the product has a large software component, such as a Shiny application. You should discuss the tasks you put on the Kanban board with the product owner, even when they are technical. This will demystify the model building and makes sure she can do a better job explaining the work to stakeholders. Especially when you are the sole data scientist on the project she also needs to get involved in prioritizing and scoping. Discussing how much time it will cost to complete the task and what it would bring can lead you to more accurate estimates of the time and value of the task. Also, the product owner might raise concerns from the business side that you did not think about, leading to a different prioritisation.